When it comes to machining, there are always a bunch of ways to do the same cut. Ask five machinists how to do a specific operation, and you’re bound to get eight different answers. Face milling is no different. When you’re looking to get a precisely-flat surface or you want a finish that really makes your part shine (literally and/or figuratively), the process of face milling can help you get there. The most common tool used when machining is an end mill. Typically, the process of cutting with an end mill utilizes both the end of the cutter, as well as the sides, which allows for pocketing and ramped cutting procedures. Face milling, in general, is defined as the process of cutting surfaces that are perpendicular to the cutter axis, or the faces of a part. Shell mills and fly cutters are most often used for face milling, but depending on what kind of surface finish you’re looking for, you could use an end mill as well.

End Mills

Using an end mill to do face milling is often inefficient, but can create some appealing patterns in your finish, if that’s what you’re after. An end mill often comes to a sharp point at one corner and the bottom edge is usually at a 1° angle as it goes to the center, so it doesn’t overlap with the previous pass. This can create some intricate patterns and surface finishes that would be hard to find elsewhere.

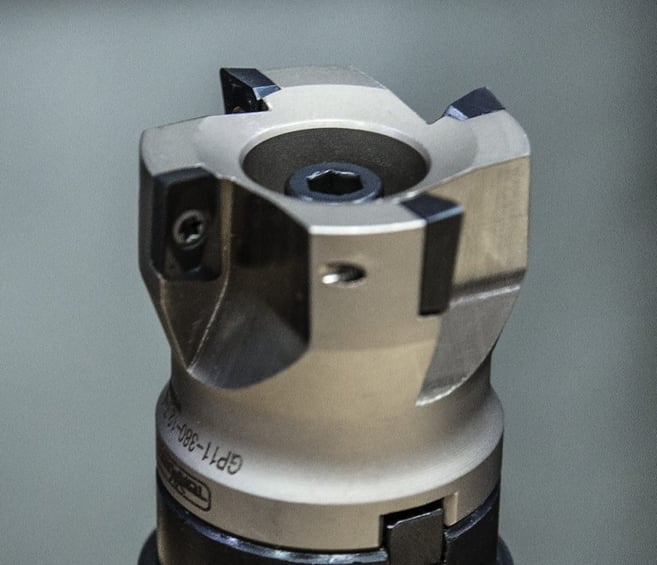

Shell Mills

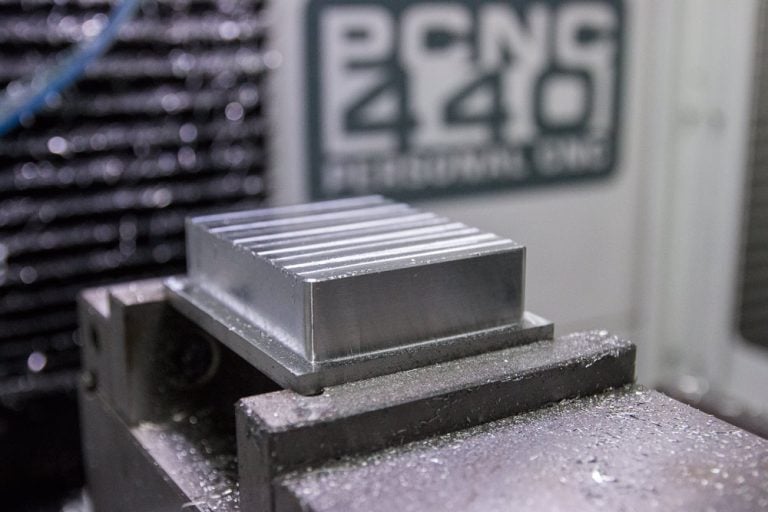

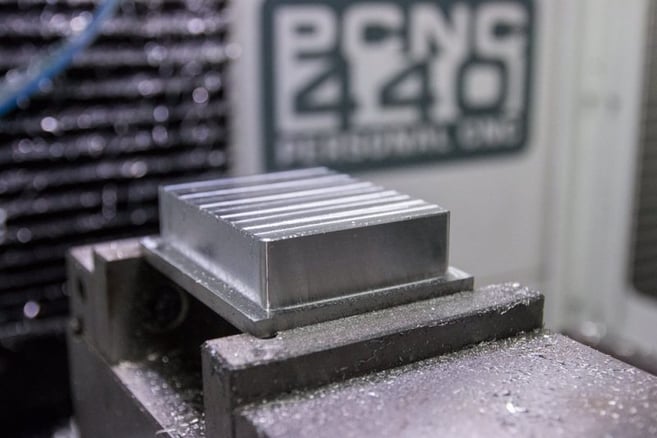

If you’re looking for a consistent finish, a shell mill is a good choice. Shell mills are also known as face mills, so they are well-known for quality face milling operations. Shell mills have several inserts on the outer edge of the cutter, so when the cutter first hits the material, it removes a small amount of stock – depending on your depth of cut. As the cutter passes over the workpiece, the other teeth actually work to remove stock that was left as a bur or as a result of the springing of the workpiece or cutter. So long as all the inserts on your shell mill are level and worn evenly, this creates a high-quality surface finish. Shell mills are also well-suited for most all materials. There may be an occasional need for the swapping of inserts for different materials, but the tool itself is robust enough to handle most all materials. While it can be considered an advantage to have multiple cutting teeth on a shell mill, having all those inserts has the potential to cause more headaches. Varying heights and subtle differences in geometries can cause varying chipload among the inserts. This won’t translate well to you surface finish

Flycutters

Shell mills provide quality surface finishes at higher speeds, while a flycutter can create a much finer finish with less horsepower. To that end, a fly cutter only uses one insert, which, while slower, can provide a more uniform surface finish. Read: The Science of Face Milling with a Flycutter If you’re looking to get fantastic surface finishes and speed per operation isn’t as much a factor, you can pick up the TTS Superfly cutter stocked with inserts for both softer materials (like aluminum) and harder materials (like steel) for less than $150.

Tips for Face Milling

First, take into account your tool stability and the horsepower in your spindle. With all those teeth and a smaller spindle, a million-tooth shell mill is going to get bogged down really fast. For Tormach machines, we recommend sticking to our shell mill if you’re going to be cutting things like steel. The 38 mm shell mill can do the operation a bit faster in harder metals, but the fly cutter with the proper inserts can also handle such operations, it’ll be a bit slower, but it can handle the cuts and still give you a nice finish. In softer materials, like aluminum, the flycutter will still give you fantastic results, or the Shear Hog has been known to get some chips flying while leaving a nice, reflective sheen. No matter what material you’re cutting, it’s usually recommended that you position the cutter off-center from your workpiece when face milling. This provides the thinnest chip at the cutter’s exit, which leads to a cleaner cut and finer finish. To this end, frequent entering and exiting of the workpiece should be avoided – it can create some stresses on the cutting edge that may result in dwell and chatter tendencies. So, keep your toolpaths on your workpiece as much as possible. For the same reason, you should also try to avoid face milling over holes or slots, because these edges cause multiple cut entries and exits. If you find it necessary to cut over surfaces with these sorts of interruptions, you can help ease the stress on your cutter by reducing the feed rate. Face milling operations are a great way to remove some material and get a nice flat surface, but the real joy comes when you get to see that surface finish. Rest assured, if you aren’t already addicted to facing, you will be when you see that shine.